Linux Overview

Linux is an open-source, privacy-focused desktop operating system alternative. In the face of pervasive telemetry and other privacy-encroaching technologies in mainstream operating systems, desktop Linux has remained the clear choice for people looking for total control over their computers from the ground up.

Our website generally uses the term “Linux” to describe desktop Linux distributions. Other operating systems which also use the Linux kernel such as ChromeOS, Android, and Qubes OS are not discussed on this page.

Privacy Opmerkingen

There are some notable privacy concerns with Linux which you should be aware of. Despite these drawbacks, desktop Linux distributions are still great for most people who want to:

- Vermijd telemetrie die vaak gepaard gaat met propriëtaire besturingssystemen

- Maintain software freedom

- Use privacy-focused systems such as Whonix or Tails

Open-Source Security

It is a common misconception that Linux and other open-source software are inherently secure simply because the source code is available. There is an expectation that community verification occurs regularly, but this isn’t always the case.

In reality, distro security depends on a number of factors, such as project activity, developer experience, the level of rigor applied to code reviews, and how often attention is given to specific parts of the codebase that may go untouched for years.

Missing Security Features

At the moment, desktop Linux falls behind alternatives like macOS or Android when it comes to certain security features. We hope to see improvements in these areas in the future.

-

Verified boot on Linux is not as robust as alternatives such as Apple’s Secure Boot or Android’s Verified Boot. Verified boot prevents persistent tampering by malware and evil maid attacks, but is still largely unavailable on even the most advanced distributions.

-

Strong sandboxing for apps on Linux is severely lacking, even with containerized apps like Flatpaks or sandboxing solutions like Firejail. Flatpak is the most promising sandboxing utility for Linux thus far, but is still deficient in many areas and allows for unsafe defaults which permit most apps to trivially bypass their sandbox.

Additionally, Linux falls behind in implementing exploit mitigations which are now standard on other operating systems, such as Arbitrary Code Guard on Windows or Hardened Runtime on macOS. Also, most Linux programs and Linux itself are coded in memory-unsafe languages. Memory corruption bugs are responsible for the majority of vulnerabilities fixed and assigned a CVE. While this is also true for Windows and macOS, they are quickly making progress on adopting memory-safe languages—such as Rust and Swift, respectively—while there is no similar effort to rewrite Linux in a memory-safe language like Rust.

Uw distributie kiezen

Niet alle Linux-distributies zijn gelijk geschapen. Our Linux recommendation page is not meant to be an authoritative source on which distribution you should use, but our recommendations are aligned with the following guidelines. These are a few things you should keep in mind when choosing a distribution:

Vrijgave cyclus

Wij raden je ten zeerste aan distributies te kiezen die dicht bij de stabiele upstream software releases blijven, vaak aangeduid als rolling release distributies. Dit komt omdat distributies met een bevroren releasecyclus vaak de pakketversies niet bijwerken en achterlopen op beveiligingsupdates.

For frozen distributions such as Debian, package maintainers are expected to backport patches to fix vulnerabilities rather than bump the software to the “next version” released by the upstream developer. Some security fixes (particularly for less popular software) do not receive a CVE ID at all and therefore do not make it into the distribution with this patching model. As a result, minor security fixes are sometimes held back until the next major release.

Wij geloven niet dat het een goed idee is om pakketten tegen te houden en tussentijdse patches toe te passen, aangezien dit afwijkt van de manier waarop de ontwikkelaar de software bedoeld zou kunnen hebben. Richard Brown has a presentation about this:

Traditional vs Atomic Updates

Traditioneel worden Linux distributies bijgewerkt door sequentieel de gewenste pakketten bij te werken. Traditional updates such as those used in Fedora, Arch Linux, and Debian-based distributions can be less reliable if an error occurs while updating.

Atomic updating distributions, on the other hand, apply updates in full or not at all. On an atomic distribution, if an error occurs while updating (perhaps due to a power failure), nothing is changed on the system.

The atomic update method can achieve reliability with this model and is used for distributions like Silverblue and NixOS. Adam Šamalík provides a presentation on how rpm-ostree works with Silverblue:

"Beveiligingsgerichte" distributies

Er bestaat vaak enige verwarring over "op veiligheid gerichte" distributies en "pentesting"-distributies. A quick search for “the most secure Linux distribution” will often give results like Kali Linux, Black Arch, or Parrot OS. Deze distributies zijn offensieve penetratietestdistributies die hulpmiddelen bundelen voor het testen van andere systemen. Ze bevatten geen "extra beveiliging" of defensieve maatregelen voor normaal gebruik.

Arch-gebaseerde distributies

Arch and Arch-based distributions are not recommended for those new to Linux (regardless of distribution) as they require regular system maintenance. Arch does not have a distribution update mechanism for the underlying software choices. As a result you have to stay aware with current trends and adopt technologies on your own as they supersede older practices.

For a secure system, you are also expected to have sufficient Linux knowledge to properly set up security for their system such as adopting a mandatory access control system, setting up kernel module blacklists, hardening boot parameters, manipulating sysctl parameters, and knowing what components they need such as Polkit.

Anyone using the Arch User Repository (AUR) must be comfortable auditing PKGBUILDs that they download from that service. AUR packages are community-produced content and are not vetted in any way, and therefore are vulnerable to software Supply Chain Attacks, which has in fact happened in the past.

The AUR should always be used sparingly, and often there is a lot of bad advice on various pages which direct people to blindly use AUR helpers without sufficient warning. Similar warnings apply to the use of third-party Personal Package Archives (PPAs) on Debian-based distributions or Community Projects (COPR) on Fedora.

If you are experienced with Linux and wish to use an Arch-based distribution, we generally recommend mainline Arch Linux over any of its derivatives.

Additionally, we recommend against these two Arch derivatives specifically:

- Manjaro: Deze distributie houdt pakketten 2 weken achter om er zeker van te zijn dat hun eigen veranderingen niet kapot gaan, niet om er zeker van te zijn dat upstream stabiel is. Wanneer AUR pakketten worden gebruikt, worden ze vaak gebouwd tegen de laatste bibliotheken uit Arch's repositories.

- Garuda: They use Chaotic-AUR which automatically and blindly compiles packages from the AUR. Er is geen verificatieproces om ervoor te zorgen dat de AUR-pakketten niet te lijden hebben van aanvallen op de toeleveringsketen.

Linux-libre kernel en "Libre" distributies

We recommend against using the Linux-libre kernel, since it removes security mitigations and suppresses kernel warnings about vulnerable microcode.

Mandatory access control

Mandatory access control is a set of additional security controls which help to confine parts of the system such as apps and system services. The two common forms of mandatory access control found in Linux distributions are SELinux and AppArmor. While Fedora uses SELinux by default, Tumbleweed defaults to AppArmor in the installer, with an option to choose SELinux instead.

SELinux on Fedora confines Linux containers, virtual machines, and service daemons by default. AppArmor is used by the snap daemon for sandboxing snaps which have strict confinement such as Firefox. There is a community effort to confine more parts of the system in Fedora with the ConfinedUsers special interest group.

Algemene aanbevelingen

Schijfversleuteling

De meeste Linux-distributies hebben een optie in het installatieprogramma om LUKS FDE in te schakelen. Als deze optie niet is ingesteld tijdens de installatie, zult je een back-up van jouw gegevens moeten maken en opnieuw moeten installeren, aangezien de versleuteling wordt toegepast na schijfpartitionering, maar voordat bestandssystemen worden geformatteerd. We raden je ook aan jouw opslagapparaat veilig te wissen:

Wissel

Consider using ZRAM instead of a traditional swap file or partition to avoid writing potentially sensitive memory data to persistent storage (and improve performance). Fedora-based distributions use ZRAM by default.

If you require suspend-to-disk (hibernation) functionality, you will still need to use a traditional swap file or partition. Make sure that any swap space you do have on a persistent storage device is encrypted at a minimum to mitigate some of these threats.

Eigen firmware (Microcode Updates)

Some Linux distributions (such as Linux-libre-based or DIY distros) don’t come with the proprietary microcode updates which patch critical security vulnerabilities. Some notable examples of these vulnerabilities include Spectre, Meltdown, SSB, Foreshadow, MDS, SWAPGS, and other hardware vulnerabilities.

We highly recommend that you install microcode updates, as they contain important security patches for the CPU which can not be fully mitigated in software alone. Fedora and openSUSE both apply microcode updates by default.

Updates

De meeste Linux-distributies zullen automatisch updates installeren of u eraan herinneren om dat te doen. Het is belangrijk om jouw besturingssysteem up-to-date te houden, zodat jouw software wordt gepatcht wanneer een kwetsbaarheid wordt gevonden.

Some distributions (particularly those aimed at advanced users) are more bare bones and expect you to do things yourself (e.g. Arch or Debian). Hiervoor moet de "pakketbeheerder" (apt, pacman, dnf, enz.) handmatig worden uitgevoerd om belangrijke beveiligingsupdates te ontvangen.

Bovendien downloaden sommige distributies firmware-updates niet automatisch. For that, you will need to install fwupd.

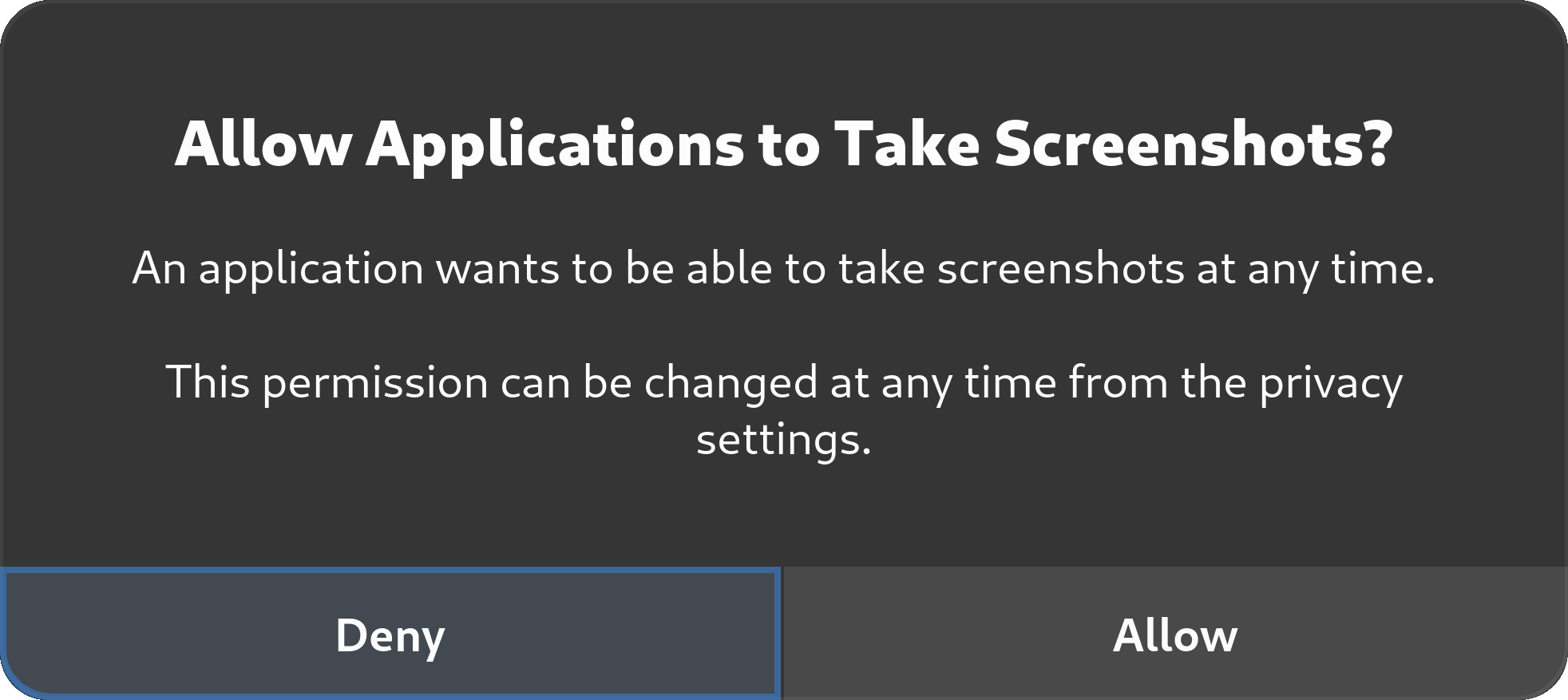

Permission Controls

Desktop environments (DEs) that support the Wayland display protocol are more secure than those that only support X11. However, not all DEs take full advantage of Wayland's architectural security improvements.

For example, GNOME has a notable edge in security compared to other DEs by implementing permission controls for third-party software that tries to capture your screen. That is, when a third-party application attempts to capture your screen, you are prompted for your permission to share your screen with the app.

Many alternatives don't provide these same permission controls yet,1 while some are waiting for Wayland to implement these controls upstream.2

Privacy Tweaks

MAC-adres randomisatie

Many desktop Linux distributions (Fedora, openSUSE, etc.) come with NetworkManager to configure Ethernet and Wi-Fi settings.

It is possible to randomize the MAC address when using NetworkManager. Dit zorgt voor wat meer privacy op Wi-Fi-netwerken, omdat het moeilijker wordt specifieke apparaten op het netwerk waarmee u verbonden bent, te traceren. Het doet niet maakt je anoniem.

We recommend changing the setting to random instead of stable, as suggested in the article.

If you are using systemd-networkd, you will need to set MACAddressPolicy=random which will enable RFC 7844 (Anonymity Profiles for DHCP Clients).

MAC address randomization is primarily beneficial for Wi-Fi connections. For Ethernet connections, randomizing your MAC address provides little (if any) benefit, because a network administrator can trivially identify your device by other means (such as inspecting the port you are connected to on the network switch). Het willekeurig maken van Wi-Fi MAC-adressen hangt af van de ondersteuning door de firmware van de Wi-Fi.

Andere identificatiemiddelen

Er zijn andere systeemidentifiers waar u misschien voorzichtig mee moet zijn. Je moet hier eens over nadenken om te zien of dit van toepassing is op jouw dreigingsmodel:

- Hostnamen: De hostnaam van jouw systeem wordt gedeeld met de netwerken waarmee je verbinding maakt. Je kunt beter geen identificerende termen zoals jouw naam of besturingssysteem in jouw hostnaam opnemen, maar het bij algemene termen of willekeurige strings houden.

- Gebruikersnamen: Ook jouw gebruikersnaam wordt op verschillende manieren in jouw systeem gebruikt. Gebruik liever algemene termen als "gebruiker" dan jouw eigenlijke naam.

- Machine ID: During installation, a unique machine ID is generated and stored on your device. Overweeg het in te stellen op een generieke ID.

Systeemtelling

Het Fedora Project telt hoeveel unieke systemen toegang hebben tot zijn spiegels door gebruik te maken van een countme variabele in plaats van een uniek ID. Fedora doet dit om de belasting te bepalen en waar nodig betere servers voor updates te voorzien.

Deze optie staat momenteel standaard uit. We raden aan om countme=false toe te voegen aan /etc/dnf/dnf.conf voor het geval het in de toekomst wordt ingeschakeld. On systems that use rpm-ostree such as Silverblue, the countme option is disabled by masking the rpm-ostree-countme timer.

openSUSE also uses a unique ID to count systems, which can be disabled by emptying the /var/lib/zypp/AnonymousUniqueId file.

-

KDE currently has an open proposal to add controls for screen captures: https://invent.kde.org/plasma/xdg-desktop-portal-kde/-/issues/7 ↩

-

Sway is waiting to add specific security controls until they "know how security as a whole is going to play out" in Wayland: https://github.com/swaywm/sway/issues/5118#issuecomment-600054496 ↩

U bekijkt de Nederlands versie van Privacy Handleidingen, vertaald door ons fantastische taalteam op Crowdin. Als u een fout, of onvertaalde secties op deze pagina ziet, overweeg dan alstublieft om te helpen! Bezoek Crowdin

You're viewing the Dutch copy of Privacy Guides, translated by our fantastic language team on Crowdin. If you notice an error, or see any untranslated sections on this page, please consider helping out!